Mary Mackey is a member of WNBA-San Francisco. She became a writer by running high fevers, tramping through tropical jungles, being swarmed by army ants, and reading. She is the author of 9 poetry collections, including In This Burning World: Poems of Love and Apocalypse (Marsh Hawk Press 2025); Sugar Zone, winner of a PEN Award; and The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams, winner of the Eric Hoffer Award for Best Book Published by a Small Press.

Where did the concept for your new poetry book, In This Burning World: Poems of Love and Apocalypse” originate?

(MM): The poems in In This Burning World are not simply a collection of unrelated poems. They form a lyrical, poetic look at what I imagine what lies ahead of us as the climate of the Earth changes; and what we can do to preserve hope, joy, and compassion in the face of a slowly evolving catastrophe. They are poems that weave together the most accurate scientific predictions I could find with the emotions we experience when we think about the New Planet that is being created around us as the glaciers melt, the forests burn; and the seas and rivers rise.

In 1966, I saw the cloud forests of Costa Rica being turned into charcoal, and as I stood there on the unpaved gravel of the Pan-American Highway watching those tall trees—with their orchids and hummingbird nests and fog-wreathed branches—tumble to the ground, I became an environmentalist before I had ever heard of the word. This was the moment when I saw the destruction that was coming, the seed that lay in my mind for decades and grew at last into the poems in In This Burning World.

What do you hope readers take away from your new book?

(MM): I hope people who read these poems will find them beautiful, absorbing, and moving. I hope these poems will help bring the science behind the predictions about climate change to life and give emotional force to the unemotional logic of scientific studies; because I believe people must be moved as well as convinced. I hope too that those who read In This Burning World will come to believe—as I do—that mutual aid and kindness are vital in the face of what the future holds for us as the Earth warms; that, if we can’t undo the effects of climate change, we still can choose to love and care for another with passionate kindness and passionate devotion; burn with the determination to shelter and comfort those who have lost everything; reach out to one another and create places where grief cannot enter. And I hope that young people living now and the generations still to born will find in these poems a reason to go on hoping, loving, and living.

How would you describe the relationship between the two kinds of burning: the burning of apocalypse and the burning of love?

(MM): One drives the other—at least I hope it does. If we only concentrate on the apocalyptic changes going on in the Earth’s climate, we risk falling into despair, becoming depressed, frozen like deer in the headlights. When you feel powerless, you give up; you do nothing. But if you concentrate on love and the power of love to unify us, there is a great deal we can do to help one another Every human being on this planet is in the same situation right now or will be in it in fairly near future. I don’t think that there has ever been a time in human history when we have all had so much in common except perhaps during the two great ice ages that humans have lived through in the past 200,000 years.

I see that you wonderfully explain how and where writers get their inspiration from in your book “Creativity: Where Poems Begin.” Where does your inspiration to use poetry as your writing medium come from?

(MM): I write poetry, novels, and screenplays. Some of my novels—particularly The Year The Horses Came, The Horses at The Gate, and The Fires of Spring, which are set in Europe 6000 years ago—have environmental themes, but they also have plots, characters, action, adventures, not to mention love scenes. All these things tend to dilute the impact of observations about the environment, which fades into the background and becomes scenery.

I am inspired to use poetry as a writing medium, because it does some things no other form writing that I know of does with such ease: First, it’s short, concentrated, and has immediate impact. When I write a poem I cut ruthlessly until I arrive at the core. For example, the poem “Cold Snap” that appeared in my collection The Jaguars That Prowled Our Dreams started out as a four page poem and ended up as three lines:

Cold Snap

dying is something you only do

once

you don’t have to get good at it

The second thing poetry can do is tolerate ambiguity. When you read a scientific paper, you expect a logical conclusion. But when you read a poem it can spread out in a myriad of different ways, take you to places where contradictions can exist together, even recreate itself and become a new poem in your mind. In other words, poetry is powerful, expansive, and unpredictable.

But perhaps the most important aspect of poetry—at least the kind of poetry I write–is that it can convey emotion better and more powerfully than most other forms of writing, and it does this in more than one way. Poetry can be beautiful and moving; powerful and life-changing; it can recreate touch, taste, and smell. A poem can not only describe what we see when we see a leaf, but what we feel when we see that particular leaf, what that leaf reminds us of, what it is to us or what it isn’t to us. Poetry can take an idea and illuminate it like a medieval manuscript. It can make unusual connections: see faces in tree trunks, messages in clouds, the penmanship of birds. Poetry is imagination set free with no boundaries.

How would you describe your writing process? Does it alter depending on which book you are working on?

(MM): All my writing starts with an idea, an image, or a few words that bubble up from some wordless space inside me. This is hard to express, but I’ve tried to describe where creative ideas come from—not just mine, but everyone’s—in a short book entitled Creativity: Where Poems Begin.

I usually write for about 5 hours a day, mostly in the mornings. I always write the first drafts of my poems in a large notebook. After I’ve revised the first draft four or five times, I enter the poem into a file in my laptop and do six or seven revisions, trying to find better words for what I want to say, encouraging and developing metaphors, playing with line breaks, and cutting ruthlessly. The finished poem—the one readers see—has usually gone through twelve or more revisions.

My process for writing novels is different. I always write novels on my laptop. I start by writing a rough plot summary (which I’m willing to change if I think of something better). I have created blank characters charts, which I fill in for all my main characters, asking myself questions like: “Age?” “Height?” “Friends?” “Enemies?” “Present Problem?” “How Will it Get Worse?” When all this preparation is done—and all the research is finished if this is a historical novel—I start writing. A novel takes me approximately two years to complete. Like poems, I put my novels through multiple revisions—usually at least half a dozen or more.

Except for the need to do historical research for historical novels, this process doesn’t change much depending on which book I’m working on. On the other hand, when I’m writing screenplays my writing process is different. If I’m adapting one of my own novels, I do a new, updated two page outline of the plot and then reconfigure it for film and turn it into a two-page, present tense treatment, which—as usual—I revise, often in collaboration with another screenwriter. The treatment becomes the basis for the screenplay. One thing I do that is a little unusual is to close my eyes and run the film in my mind from start to finish. I do this several times as I polish and revise the screenplay.

How did being a woman shape your experience as a writer?

(MM): When I was young, almost all editors and the majority of agents were male. Women writers were not taken seriously—particularly women poets who were often mocked and thought fit only to write greeting cards. In college I did manage to get a poem accepted by the editors of the undergraduate literary magazine by imitating a poem by Wallace Stevens, which was “male” enough to pass the test; but for the most part, it too was an almost-all-male publication.

At the time, this was frustrating and discouraging, but as the years passed it became clear to me that this lack of acceptance had been a good thing. If my poetry had been welcomed, I would probably have gone on imitating male writers. Instead, I was able to find my own voice—a female voice, individual, personal, not like anyone else’s. And when I began teaching, I was able to help other women find their voices.

More importantly, I became part of a community of women. The year I graduated from college, 1966, was a time when women and people of color were redefining what it meant to be a writer. Women were founding presses like Shameless Hussy Press, which published my first novel Immersion (which was quite probably the first Second Wave feminist novel in the world published by a Second Wave feminist press.). They were creating women’s bookstores and literary magazines like Velvet Glove and Yellow Silk Journal, which published my poetry. I will forever be grateful to the women writers, editors, agents, teachers, librarians, friends, and colleagues who helped, supported, and encouraged me over the years. Without them, I might never have become a writer.

Climate change continues to be a pressing issue for our world. How does your passion for ecology and history tie into your book concepts of the “New Planet” and “Old Planet”?

(MM): In In This Burning World, the “Old Planet” is the planet we’re living on right now, the one we have inhabited for nearly 12,000 years since the end of the last Ice Age. This Old Planet is changing all around us at an increasingly accelerating rate. The “New Planet” is whatever the Earth will be like in the future.

This concept of the Old and New Planet is a natural outgrowth of a lifelong interest. I write historical novels and enjoy doing the research needed to make the history in them as accurate as possible. As for ecology, I’ve been passionate about it ever since I spent months living in remote tropical field stations in the jungles of Central America surrounded by ecologists who taught me about biodiversity, ecological niches, and why hummingbirds have mites in their noses.

A knowledge of ecology and an awareness of potential changes in the environment such as rising sea levels and rising global temperatures, suggests that the New Planet may be very different from the Old Planet. A knowledge of history tells us that radical changes in an environment eliminates entire species. The question that haunts me, the one that I think we all might want to ask ourselves, is: “Will there be a place for us on this New Planet that we’ve been helping create? No one knows for sure. But poets can imagine where scientists can only reason, and poems can bring what poets imagine to life.

What advice would you give to any aspiring female writers?

(MM): It’s the same advice I’d give to any aspiring writer: Write for fun. Play with your writing. Write freely without worrying about getting published. Write whatever you want. The truth is, there aren’t any rules when it comes to writing; so make up your own. Start a small in-person writing group and share your work with other writers who are at about the same stage in their careers as you are. In my first writing group, none of us had been published and it felt as if we never would be; but we helped and encouraged each other, and as of 2025, the three of us have had over thirty novels published by major publishers and small presses. So don’t get discouraged by rejection. Just keep writing. And revise, revise, and revise.

Mary Mackey’s poetry has been praised by Wendell Berry, Jane Hirshfield, D. Nurkse, Al Young, Daniel Lawless, Rafael Jesús González, and Maxine Hong Kingston for its beauty, precision, originality, and extraordinary range. She is also the author of 14 novels including The New York Times bestseller A Grand Passion.

My journey to the

My journey to the CJ Palmisano has written since she could scribble “no” on her mother’s immaculate kitchen wall. She has never stopped writing–a few pages here, an entire story there–but for the majority of her adult life, writing couldn’t be a priority. She raised a family and taught, something she did well (for what it’s worth, in 2006 she was in Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers).

CJ Palmisano has written since she could scribble “no” on her mother’s immaculate kitchen wall. She has never stopped writing–a few pages here, an entire story there–but for the majority of her adult life, writing couldn’t be a priority. She raised a family and taught, something she did well (for what it’s worth, in 2006 she was in Who’s Who Among America’s Teachers). A Substack Fairy Tale Success: Building Your Readership and Platform with Kate Farrell

A Substack Fairy Tale Success: Building Your Readership and Platform with Kate Farrell Kate Farrell, storyteller, author, librarian, founded the California Word Weaving Project: Learning through Storytelling; published numerous educational materials on storytelling, and contributed to and edited award-winning anthologies of personal narrative. Farrell’s award-winning recent book is a how-to guide on the art of storytelling,

Kate Farrell, storyteller, author, librarian, founded the California Word Weaving Project: Learning through Storytelling; published numerous educational materials on storytelling, and contributed to and edited award-winning anthologies of personal narrative. Farrell’s award-winning recent book is a how-to guide on the art of storytelling,

Publisher AMA

Publisher AMA Kat Georges is a poet, playwright, editor, publisher, and graphic designer. She is co-director and an acquisitions editor for Three Rooms Press, an independent publisher inspired by diversity, dada, punk, and passion. Her most recent book is the poetry collection Awe and Other Words Like Wow, and she is co-editor of MAINTENANT, the annual journal of Contemporary Dada Writing and Art. She lives in New York City. Kat is currently looking for LGBTQ+ fiction and young adult fiction that deal directly with current anti-queer attitudes, mysteries that center on bold and daring diverse main characters, and riveting women of history who need to have more attention given to them. Kat welcomes voices that have something different to say, that inspire readers, and that shows the power of innovative, compelling writing. To see the latest Three Rooms Press releases, visit

Kat Georges is a poet, playwright, editor, publisher, and graphic designer. She is co-director and an acquisitions editor for Three Rooms Press, an independent publisher inspired by diversity, dada, punk, and passion. Her most recent book is the poetry collection Awe and Other Words Like Wow, and she is co-editor of MAINTENANT, the annual journal of Contemporary Dada Writing and Art. She lives in New York City. Kat is currently looking for LGBTQ+ fiction and young adult fiction that deal directly with current anti-queer attitudes, mysteries that center on bold and daring diverse main characters, and riveting women of history who need to have more attention given to them. Kat welcomes voices that have something different to say, that inspire readers, and that shows the power of innovative, compelling writing. To see the latest Three Rooms Press releases, visit  Catherine Lawrence has spent the majority of her career as an Administrator in the field of Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn). In this capacity, Catherine has helped students navigate University programs at the Undergraduate and Graduate levels. While working full time Catherine completed her Undergraduate and Graduate degrees (in the evening) receiving a B.S. in Communication, Political Science and History; as well as a M.S.Ed in Education (Reading, Writing and Literacy/Adult, Family and Community) with a certification as a Reading Specialist.

Catherine Lawrence has spent the majority of her career as an Administrator in the field of Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn). In this capacity, Catherine has helped students navigate University programs at the Undergraduate and Graduate levels. While working full time Catherine completed her Undergraduate and Graduate degrees (in the evening) receiving a B.S. in Communication, Political Science and History; as well as a M.S.Ed in Education (Reading, Writing and Literacy/Adult, Family and Community) with a certification as a Reading Specialist.

Speaking for Authors Lunch N Learn Fireside Chat

Speaking for Authors Lunch N Learn Fireside Chat Bobbie Carlton is the founder of three companies, Carlton PR & Marketing, Innovation Nights, and Innovation Women, an online “visibility bureau,” dedicated to providing women and other underrepresented voices with a chance to be seen as thought leaders and experts.

Bobbie Carlton is the founder of three companies, Carlton PR & Marketing, Innovation Nights, and Innovation Women, an online “visibility bureau,” dedicated to providing women and other underrepresented voices with a chance to be seen as thought leaders and experts.  Debra Eckerling is an award-winning author and podcaster, goal-strategist, and speaker, who helps authors, entrepreneurs, and consultants create the life they want through goals. Debra speaks on the topics of setting personal and professional projects, networking strategy, and

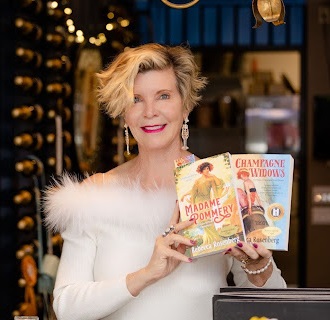

Debra Eckerling is an award-winning author and podcaster, goal-strategist, and speaker, who helps authors, entrepreneurs, and consultants create the life they want through goals. Debra speaks on the topics of setting personal and professional projects, networking strategy, and  When Rebecca Rosenberg discovered the real-life widows who made champagne a world-wide phenomenon, she knew she’d dedicate years to telling their stories. These remarkable women include Veuve Clicquot, Madame Pommery, and Lily Bollinger.

When Rebecca Rosenberg discovered the real-life widows who made champagne a world-wide phenomenon, she knew she’d dedicate years to telling their stories. These remarkable women include Veuve Clicquot, Madame Pommery, and Lily Bollinger.